This blog is part of a two-part series about our incubator, Beta’s, collaboration with Young 1ove on the “No Sugar” intervention. Check out part one in this series here.

The idea was compelling: show adolescent girls the dangers of engaging in transactional sex with middle-aged men, using data (HIV prevalence rates disaggregated by age and gender), video content and an interactive discussion, to reduce their risk of contracting HIV.

It seemed promising: many girls in low- and middle-income countries actually think older partners are safer partners, and see sugar daddies as offering financial gain with little downside – which is why sugar daddies are a key driver of the disproportionately high rates of HIV infection among girls and women globally.

Most importantly, it was evidence-based: a 2005 randomized controlled trial conducted in Kenya found that girls who were told about the dangers of sugar daddies were 28% less likely to be pregnant at year-end than girls who were simply told to abstain, and girls who received no sexual education beyond that offered in school.

Based on this success, and with financial support from the Global Innovation Fund, Young 1ove worked with a group of partners, including the Government of Botswana, the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL), Botswana-Baylor Children’s Clinical Centre of Excellence, and Evidence Action, to evaluate the idea again through a similar program, No Sugar, piloted in Botswana. This second round of evaluation, however, delivered mixed results, as we highlighted in an earlier blog post. Consequently, all partners involved in the program made a decision not to scale the No Sugar intervention.

LESSONS FOR THE FUTURE

Why did these two evaluations yield such different results? According to our partner, Young 1ove, there may be several reasons, many of which are outlined in Young 1ove’s 2016 annual report and on their website. An upcoming working paper analyzing the results will provide even more insights on this and other lessons learned along the way. In the meantime, here are our three biggest takeaways from the experience which may be most relevant to implementers, policy-makers, and researchers:

#1: Sugar daddies weren’t Just middle-aged men — they were mostly in their 20’s.

“Sugar daddies were younger than we thought: 20-year-olds not 40-year-olds” –

Young 1ove, 2016 Annual Report

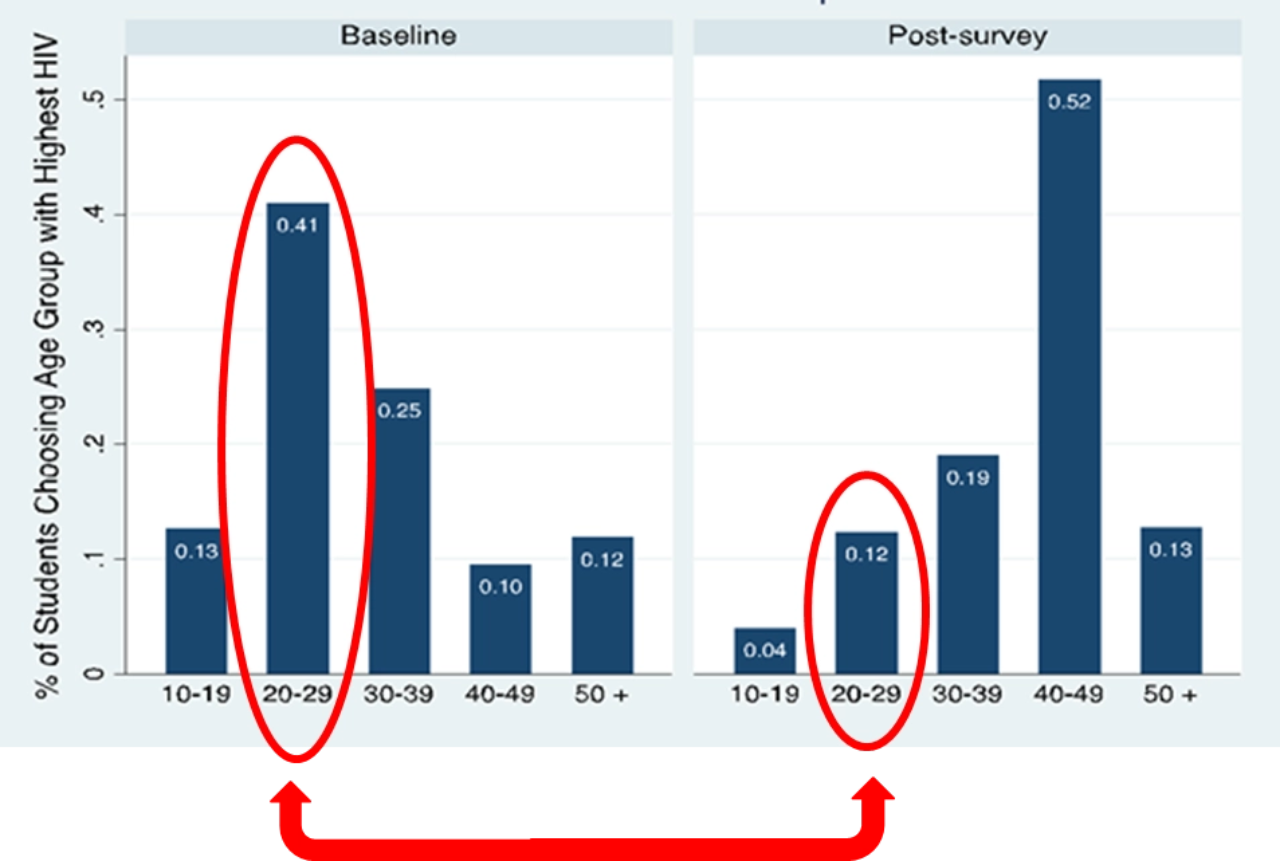

Before hearing the ‘relative-risk’ message in the No Sugar curriculum, most students thought that men in their 20’s or 30’s had the highest rates of HIV infection. Immediately after the hour-long class, over half of the students were able to correctly identify 40-49 year old males as the highest risk group. This knowledge did decay over time, but at least initially, there was that gasp of awareness as their preconceived notions of relative risk shifted dramatically.

If most sugar daddies are in their 40’s, then this is exactly what we’d hope for: a shift in understanding that could translate into changes in partner choice away from men in their 40s. However, the data revealed a different story. Most sexually-active girls indicated that their sexual partners were in their 20’s—not their 40’s. That doesn’t mean these girls are safe: relationships with 20-year-olds are still significantly riskier for preadolescent and adolescent girls than relationships with their peers. However, it does mean that the program may have unintentionally taught girls that their typical sexual partners, men in their 20’s, are less risky than they originally thought.

This is the opposite of the intended effect of the program, and raises concerns about the potential for causing harm. Policymakers and practitioners delivering (or considering) an anti-sugar-daddy, HIV relative-risk information campaign should consider this dynamic very carefully.

#2: Girls today may prioritize managing pregnancy risk over HIV risk

“Girls care about the risks of getting pregnant as much or more than HIV” – Young Love, No Sugar FactSheet

The research on which No Sugar was based took place over a decade ago. At the time, the number of people living with HIV globally had peaked at over 40 million people. Meanwhile, access to antiretroviral treatment was limited: only one in ten Africans in need of treatment was receiving it. That made the costs of contracting HIV exceedingly high: more than three million people died of AIDS-related illnesses in 2005 and in Botswana, 77 percent of all orphans lost at least one of their parent to AIDS in the same year.

Times have changed. In 2016, AIDS-related deaths had fallen by nearly a third and over 54 percent of HIV positive individuals in East and Southern Africa had access to antiretroviral treatment. In Botswana, 89 percent of HIV-positive people aged 15-59 are on antiretroviral treatment. It is possible that the global progress in the fight against AIDS, and in reducing the stigma associated with it, has made the disease less scary for younger generations who now know that it is possible to live near-normally with HIV.

On the other hand, pregnancy often leads to to girls dropping out of school, and has immediate and visible life consequences. Of course, this hypothesis would need to be explored further, but if it is the case that girls have become less fearful of exposure to HIV risk relative to the risk of getting pregnant (as Young 1ove’s analysis indicates), then information campaigns focused on managing HIV risk may be much less effective now than they were a decade ago. For a relative-risk campaign to be effective, it must be rooted in an understanding of modern girls’ priorities and motivations.

#3: Have a pre-policy plan

It’s become more and more common in the world of randomized evaluations for investigators to submit pre-analysis plans — a step-by-step plan which lays out how a researcher will analyze a set of data in advance of having the data in hand. This practice increases the reliability of the results, and reduces the negative effects of data-mining, publication biases, and other subjective forces once that data rolls in.

Inspired by this trend, and aware that the interpretation and application of evaluation results to policy decisions can be subject to similar pressures and biases, the partners embarked together on articulating and committing to what we dubbed a ‘pre-policy plan’. Like a pre-analysis plan, the ‘pre-policy plan’ laid out in advance the intended policy responses and potential scaling path for No Sugar depending on the range of potential outcomes of the evaluation – before those results were available – creating an important commitment device for the partners.

This engagement before and during the evaluation, undertaken by a team of stakeholders including implementing partners, evaluators, donors, and the Government of Botswana, was intended to motivate and generate commitment for an evidence-based response, whatever the results would ultimately be. A commitment to take action towards scaling the program if the evaluation results showed clear evidence of positive impact, namely a clear and statistically significant reduction in pregnancy rates, a clear indication that girls learned and retained knowledge about the HIV prevalence of different age groups, and a downward shift in the age of girls’ sexual partners. But also a commitment NOT to proceed with scaling the program unless that evidence was clear.

Critically, we had this discussion early—well before the evaluation results were in—guaranteeing that it was sober-minded, reflective of what partners believed to be the most appropriate response to ambiguous or negative results, and unclouded by genuine but unfounded enthusiasm for a program that might ‘feel right’ but not be grounded in evidence.

Ultimately, in reviewing the preliminary results of the No Sugar evaluation, all partners, including the Government of Botswana, agreed not to scale the program. Partners were able to reach this consensus easily because we had defined what would constitute positive results, discussed beforehand the possibility of negative and ambiguous results, and agreed on our response to each of the different potential evaluation outcomes. Ultimately, by collectively exploring the possibility of evaluation “failure”—which is not an easy thing to consider and discuss—the Government of Botswana avoided the real failure: investing substantial public resources in a program lacking concrete proof of impact.

One of our biggest takeaways from participating in the No Sugar journey has been the need for exactly this type of systematic planning for all possible results of an evaluation, and the value in investing in these conversations ex ante. To maximize accountability and commitment, it’s important that this scenario planning process involves all major stakeholders in a program, including policy-makers, donors, implementers, and those providing technical assistance, and that these parties agree in advance to a pre-policy plan that outlines responses to a range of possible evaluation outcomes.

As we incubate and test new initiatives at Evidence Action through our Beta incubator, we’re creating mechanisms, such as pre-policy plans, that ensure these strategic conversations about the interpretation and application of results happen. It’s one of the ways we’re helping to transform the path from Evidence to Action.

Photo Credit: Young 1ove. Results and lessons [Unpublished presentation, 2017]