Safe drinking water was recognized as a human right nearly 15 years ago – yet over 2 billion people around the world use a contaminated drinking water source. This causes over 1 million preventable deaths annually from diseases like typhoid, cholera, hepatitis A, or child diarrhea. Paradoxically, our most essential natural resource can also present one of the greatest threats to life.

In the 1990s, the global picture was even worse – and in Nicaragua, less than half the country had access to safely managed drinking water services. This had devastating consequences – child mortality was over ten times higher than in high-income countries.

It was in this dire context in Nicaragua that Fred and Charles came up with a solution that, decades later, will save tens of thousands of lives.

Existing technology “didn’t work for more than a couple days”... “saw a million of them sitting by the roadside.”

Against this backdrop of high levels of unsafe water, there was no dependable commercial device on the market to make water drinkable. Available options like sand filters, solar filters, or drip chlorination were unreliable – some only worked for a few days, and it was common to see “a bunch littered by the roadside in rural communities that were just rusting away, or [taken] apart to use the pieces for something else.”

As is still common today, NGOs operating in Nicaragua were more focused on water access than water safety, investing tens of millions in building water infrastructure (e.g., wells, boreholes). Yet they had no way to clean the water, ultimately providing contaminated water to rural communities.

Fred Jacob wanted to change that.

As an Operations Manager at Taller de Agua y Salud Campesina (TASCA), an NGO focused on water and rural health, Fred started searching the early internet for alternate solutions. He found Compatible Technology International (CTI) – a volunteer organization focused on developing practical, affordable food and water tools in Central America and Sub-Saharan Africa. CTI connected Fred to Charles Taflin, a civil engineer and retired superintendent of the Minneapolis, Minnesota water treatment plant.

They both knew chlorination – a proven standard for water treatment – was the right solution. They just needed the right delivery system.

It’s pretty easy to design a complex system – but to design a simple system – that is a challenge.

Fred and Charles set their sights on an ambitious goal: building a zero maintenance solution that could provide chlorinated water for small mountain villages with no electricity, no mechanical or moving parts, easily sourced materials, and installable in long water distribution lines.

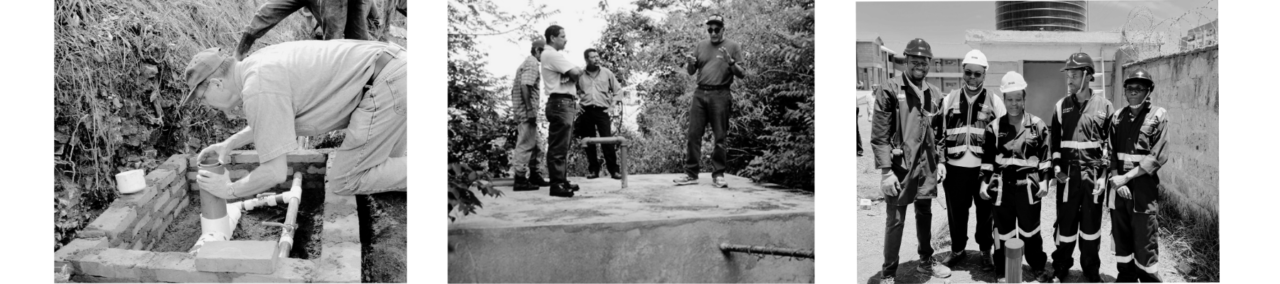

Charles started designing prototypes in his garage. At Saint Paul's water treatment plant, the Water Utility Director, a friend, lent lab technicians, and they set up a testing station in the plant's basement. Across 2.5 years, this informal team tested multiple designs across conditions and flow rates, measuring impact on chlorine dosage.

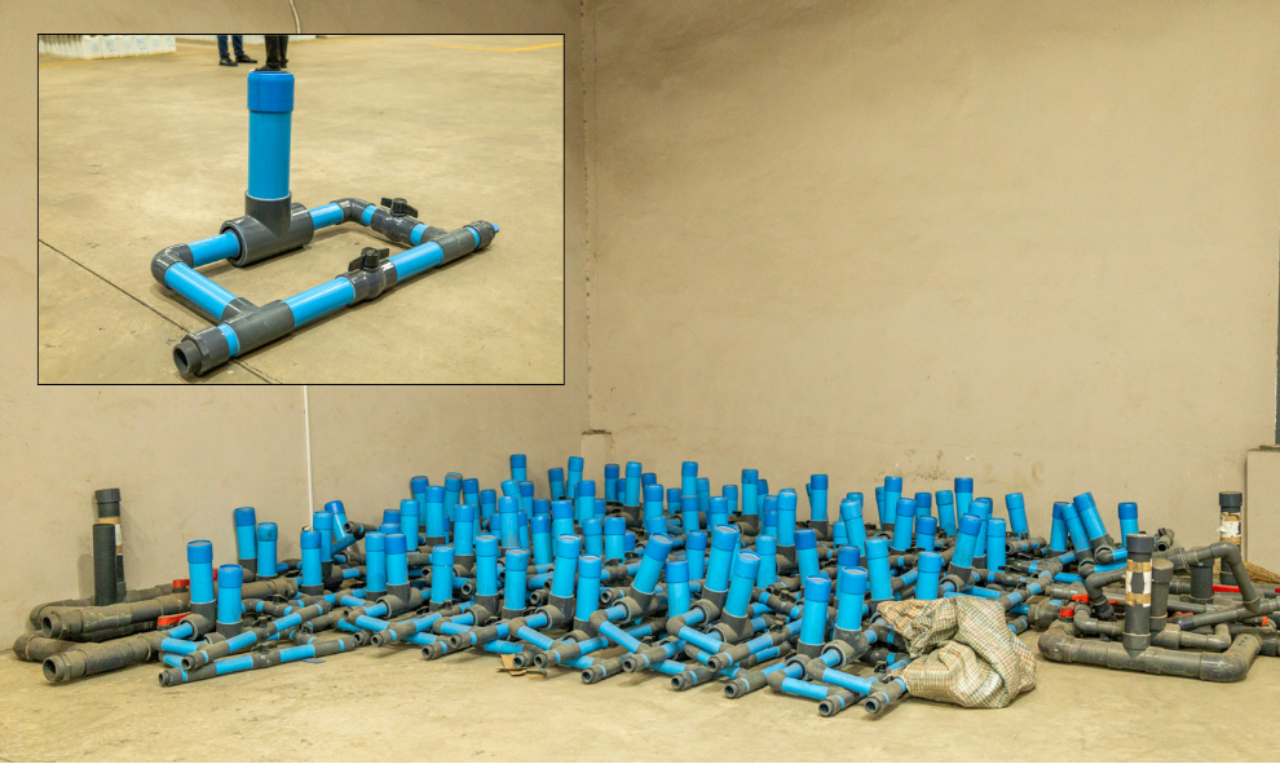

In February 2001, they reached the 8th model: The CTI-8, or “Manual Chlorinator” – a device made of PVC pipes that could be purchased at any hardware store in Latin America. It was gravity-based, able to be installed in existing water systems, and worked in low water flow environments and small water systems.

This style of iterative, evidence-based design mirrors Evidence Action’s own approach – but it remains otherwise rare in the sector. This was even more pronounced in 2001, before the randomista trend had begun in full: Two major research organizations: J-PAL and IPA, were founded in 2003 and 2002 respectively.

“This should go everywhere:” One of the earliest examples of modern open sourcing in the development sector.

TASCA launched a Manual Chlorinator pilot in Chilamate, Matagalpa in 2001. There, they began working with Sergio Romero, a Nicaraguan epidemiology technician for the Ministry of Health (MINSA). Sergio had over 20 years experience overseeing rural health issues, and helped them scale to 21 installations in gravity-fed water systems in northern Matagalpa and Jinotega Departments.

Instead of patenting, Fred and Charles decided to draft an operating manual and make it available to all on the internet – likely one of the earliest examples of modern open sourcing in the development sector.

For context – this was within a few years of Google being in beta, and Wikipedia had just launched in January. Fred and Charles put themselves at the vanguard of evidence-based practice sharing on the internet – and in doing so, laid the groundwork for this technology to scale globally.

“We were the best show in town” – but “good intentions don’t make a good project.”

CTI quickly defined a successful operational model in Nicaragua, built on support from government health and water ministries, and a strong community engagement model that leveraged existing community water and sanitation committees. Word of mouth on the Manual Chlorinator’s impact – including reductions in illness and childhood diarrhea – spread, driving requests for expansion to new villages.

Upon entering a new village, they’d “often wind up entertaining the whole village” – everyone was interested in it. The team would bring a chlorinator, demonstrate assembly/disassembly, and train water coordinators on what was required for ongoing upkeep. Villages then could choose to buy the chlorinator, creating an ongoing economic and practical investment in the project. They could also purchase chlorine tablets from TASCA, which used a rotating fund to keep prices low while allowing a small profit to fuel ongoing expansion.

This model spread rapidly – Sergio became a full-time Project Director in 2008, leading the team to install 400+ devices reaching over 500,000 people in Nicaragua. “The best invention in the world is useless if it isn't used, and Sergio provided the energy, skill, and ability to connect with the rural communities,” Fred told us.

TASCA set their sights on expansion to Honduras and Guatemala. But in these new geographies, the model hit roadblocks – in Guatemala, government health and water ministries didn't have capacity to support the work, and in Honduras there were no community water committees to help run it. This type of obstacle is common even today in the sector – where complex delivery challenges prevent replicability across contexts.

“I had thought the project was dead.”

With time came fundraising and operational constraints – the founder of TASCA passed away and the NGO was dissolved, leadership changed at CTI, and donors were hard to find. Fred and Charles maintained ongoing operations, but otherwise, “I had thought the project was dead,” shared Charles.

Following recent research showing “water treatment is one of the most cost-effective ways to improve child survival,” Evidence Action prioritized scaling in-line chlorination – and vetted the Manual Chlorinator.

New evidence quantifies something that, deep down, we already knew: Safe water saves lives. Nobel Laureate Michael Kremer’s groundbreaking study shows it reduces under-five child mortality by 25%. Evidence Action’s Safe Water Now program, launched in 2013 with chlorine dispensers, has reached over 9 million people, enabling safe water delivery in rural areas with non-piped water access. To drive further reach, our team set out to assess feasibility of scaling in-line chlorination in piped systems.

In-line chlorination was vetted through Evidence Action’s rigorous six step Accelerator process for assessing new interventions. Six devices, sourced in-part from researchers developing a meta-analysis on in-line chlorination, were tested across metrics such as durability, ease of installation and refilling, ability to adjust chlorine dose, and consistency of dosing.

The winner: The CTI-8 Manual Chlorinator – Charles and Fred’s design, honed in the basement of Saint Paul’s water treatment plant.

Within Safe Water Now, the chlorinator has reached 172,000 people – with potential to reach millions more.

Evidence Action has launched in-line chlorination in Malawi and Uganda, providing safe water access to over 172,000 people and over 20,000 children under 5 years old. We are continuing to rapidly scale this work – for example, we are partnering with the government of India on safe water delivery in two states with ambitions to scale nationwide; building on the government’s $45 billion investment in water infrastructure.

This work is at the frontier of safe water delivery – encountering first-of-their-kind delivery and community engagement challenges like Fred and Charles faced as they expanded.

Across our work, we coalesce leading academics, in-house engineering labs, and top-of-field experts to innovate on technology – and a question on flow rate initially put us in touch with Fred. We’ve tackled:

- Accounting for high-volume & pressure flow & preventing flowback (common during heavy rains)

- Testing smaller tanks via an updated, compact design

- Iterating for faster, safer ground-level installation (versus on top of tanks up to 32 feet high)

- Addressing new markets with substantial unmet need: peri-urban areas, informal settlements

- Testing solutions for multi-village schemes (sites providing water to tens of thousands of people)

In initial conversations, we learned both Fred and Charles “had no idea…that the chlorinator existed anywhere outside of Nicaragua.” The blueprint they developed – from early days iteration in the basement of a Minnesota water treatment plant, to rural Nicaragua implementation, to the open sourced operational manual uploaded to an early TASCA website – has been integral in charting a path to the first generation raised on clean water.

Photo gallery