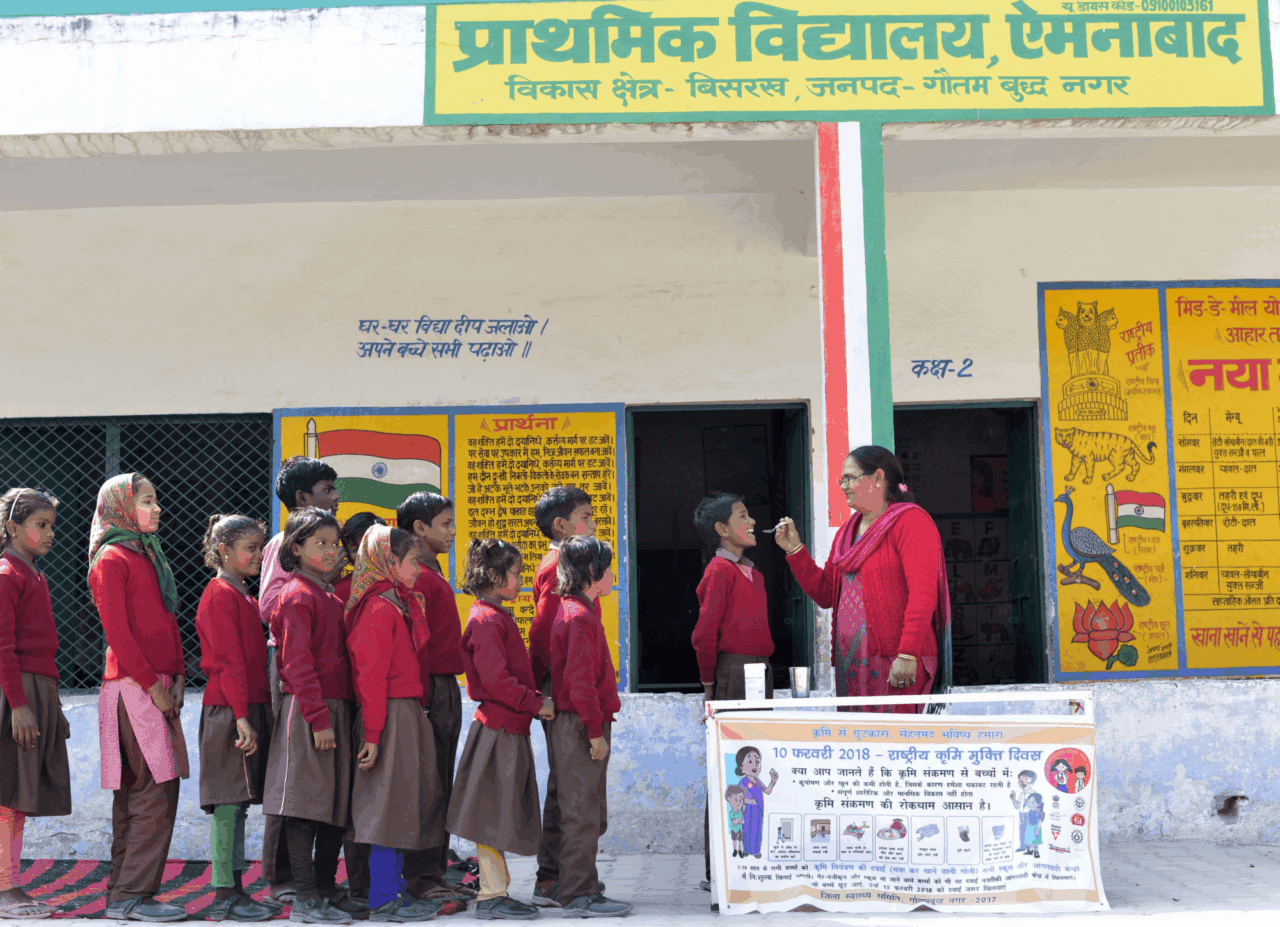

For five years we’ve worked with the Government of India to deworm up to 260 million preschool and school-age children through National Deworming Day (NDD), under the banner of our Deworm the World Initiative. Driven by our commitment to evidence, scale, and cost-effectiveness, we’ve focused keenly on developing robust data collection and monitoring processes to accurately assess how many children the program reaches (coverage data) and how well the program is delivered in schools and preschools, known as anganwadis, across the country (process monitoring data).

When National Deworming Day was initially launched in 2015, many data collection processes were paper-based, creating opportunities for human error and compromised data quality. Coverage data, for example, was manually collated at schools and anganwadis where deworming is conducted, before being transmitted upward to block, district, state, and, eventually, national levels (see figure below). At each stage of transmission, the data needed cleaning, meaning it could only be meaningfully analyzed once it reached the national level. While this approach was feasible – though not optimal – it needed rethinking as the program was scaled up across the country in February 2016.

Figure 1: Flow of data through the reporting cascade in paper-based and digital systems (smallest administrative levels to the highest).

Over the years, we’ve worked with the government to progressively digitize data collection, improving our monitoring efficiency and the quality of program data. Below we share some strategies, tools, and innovations we’ve turned to or created in the process, and what we’ve learned along the way.

Improving Coverage Data Collection

National Deworming Day (NDD) app

In 2016, we developed and rolled-out the NDD app: a software application accessible via web and mobile that has made it easier to collate and report coverage data. The app is designed to be used by government officials at the block level – once they receive data from schools and anganwadis where deworming treatment has been delivered, they input it into the application. Unlike the paper-based method, the app has ensured the identification of data errors and allowed faster data analysis by making clean, accurate data available for districts to approve. Additional features within the app prevent duplication or fabrication of data, ensuring authentic data aggregation.

Pilot of SMS reporting

We also piloted an SMS-based reporting system in 2016. The system allowed school principals to directly report the number of school-enrolled children dewormed using their phones. While the pilot test in the state of Uttar Pradesh found the system feasible for schools to use and able to provide information, ultimately the text service came at a cost and maintaining an updated database of teachers’ and health workers’ phone numbers was challenging. With implications for scalability and cost-effectiveness, these issues meant that the pilot wasn’t immediately scaled – though we remain open to technology-based direct reporting options.

Mid-May Meal platform for NDD reporting

In 2017, the state of Bihar piloted the use of a state-level Integrated Voice Response System (IVRS) for monitoring India’s Mid-Day Meal Scheme – a national program that provides lunches in public primary schools. The system includes an automated helpline that headmasters call daily to report how many children in their school are reached by the mid-day meal program. The pilot’s success led NDD partners to leverage the same IVRS-based platform for reporting treatment numbers on deworming day. Earlier this year, states such as Chhattisgarh, Uttarakhand, Bihar, Jharkhand, and Tripura trialed this approach, and we’re exploring the potential to scale it to other states.

Leveraging the IVRS system has several benefits, including the fact that it allows for real-time reporting on deworming day, which means the data can inform any course-correction that is needed between NDD and the mop-up day that follows soon after, when children who were not in school during NDD can receive treatment. However, the existing IVRS platform is designed only to report data on school children between grades 1 to 8 – the target demographic reached by the Mid-Day Meal Scheme – whereas India’s NDD targets children aged 1-19.

Improving Process Monitoring Data Collection

Google Forms for real time data monitoring

To improve process monitoring data collection, in 2016 we designed and piloted a Google form version of the monitoring checklist provided in the NDD operational guidelines. Field monitors visiting schools and anganwadis enter data directly into the form, and the data is automatically compiled and visualized into graphs. This system was scaled throughout all the states we support in 2017 and has since been adopted by all state governments.

CAPI for improved process monitoring and coverage validation

In 2016 we also introduced computer-assisted personal interviews (CAPI) to the monitoring and verification process to enable field monitors to record survey responses from teachers, children, and parents using a smartphone, tablet, or laptop. CAPI-based surveys offer real-time data collection, help authenticate fieldwork, and reduce time and costs of data compilation. Monitors also provide their signature on the CAPI-enabled tablet and add photos of schools and anganwadis they visit, as an additional means of data verification.

The Future of Tech-Enabled Data Reporting for National Deworming Day

Increasing tech-enabled data reporting for the NDD program is key to improving the quality of data collected, increasing the efficiency of data collection, and enhancing the overall cost-effectiveness of the program. Having better, faster data helps us identify areas where the quality of program delivery can be improved, and helps all stakeholders to be more accountable for programmatic excellence. We continue to explore options for further digitization of data collection, iteratively improving program quality and reach to the hundreds of millions of children treated by the NDD program in India.