Despite a vast universe of potentially high-impact interventions in the global health and development space, many good interventions with the proven ability to reduce the burden of poverty are not currently being delivered at scale. The available funding and capacity in this space are not always employed to maximize impact on the health and well-being of persons with the greatest needs. Evidence Action was founded with this challenge in mind – our mission is to scale only those interventions that have the greatest cost-effective impact on the global burdens of poor health and poverty.

We maximize the impact of our and our donors’ investments, enabling us to reduce poverty for millions.

Though this may sound simple, screening potential interventions to determine which deliver the most benefit for the lowest cost is a complex task. Our unique, robust, and objective-focused process — what we call our Accelerator — happens largely behind the scenes. In this post, we take a deeper dive into our framework, exploring the immense value we see in this engine of new program development.

What is the Accelerator and why is it important to Evidence Action’s work?

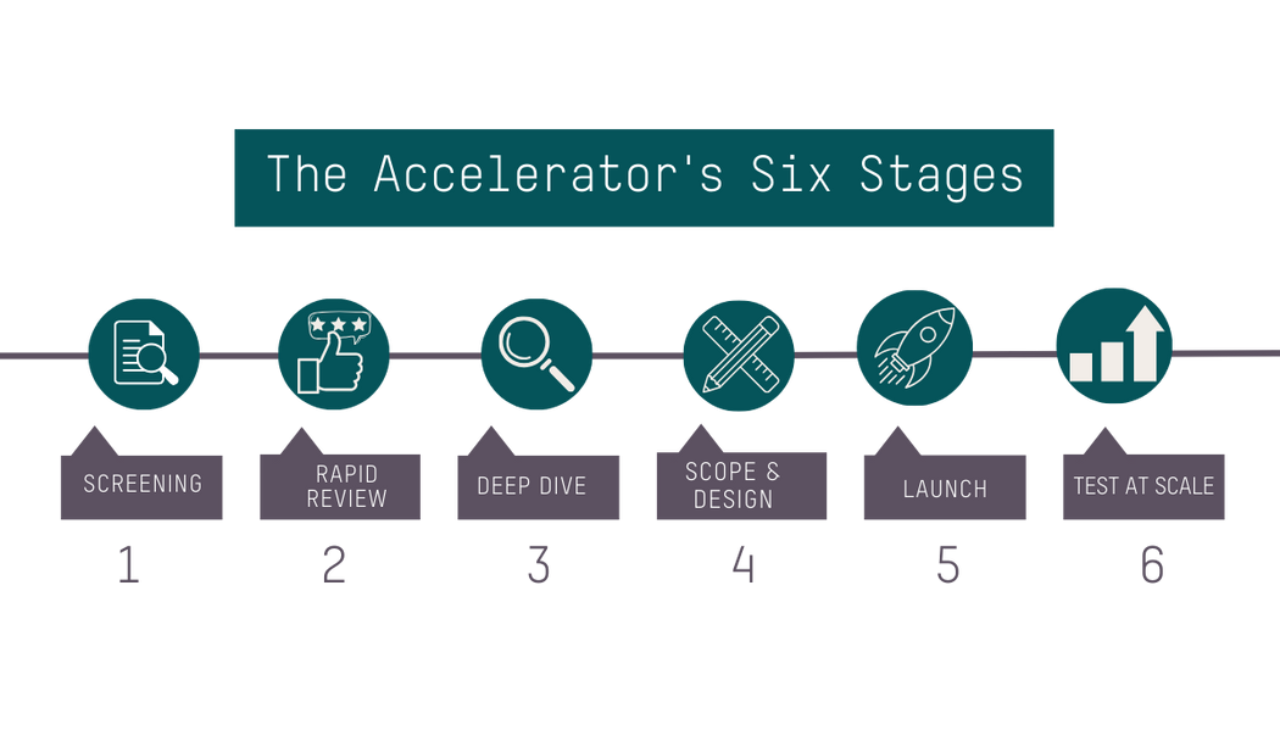

Broadly, the Accelerator develops programs using a six-stage, decision-focused process designed to scale only the most cost-effective, evidence-based interventions. The process is built to ensure that we identify as many foreseeable challenges to scaling and solutions as possible, and to hold us accountable for prioritizing only those interventions that best align with our organizational values and with our core principles of evidence, cost-effectiveness, and scale. In this way, we maximize the impact of our and our donors’ investments, enabling us to reduce poverty for millions of people.

How does the Accelerator identify and prioritize interventions for research?

We identify interventions for Accelerator research through several different methods. Ideas are sourced prior to the first stage of our process, most often through reviewing existing lists compiled by other organizations or experts. For example, this Lancet review article helped us source interventions of interest in the maternal nutrition space, and we often use WHO guidelines to help identify promising solutions. We find this to be a valuable method of sourcing because it saves time while maintaining our focus on credible, evidence-based interventions.

The second major way we source interventions is through our existing program and country teams. These teams have valuable insights into the needs of communities and priorities of the governments in countries where we currently work. In addition, ideas may come from other pathways, including external stakeholders, researchers, or donors; so long as they are aligned with our mission, the Accelerator will consider them.

Because we continuously source ideas, the Accelerator usually has a long list of interventions that are ready to enter the first stage of evaluation – and prioritization is necessary. At the beginning of our process when not much is known about the intervention, we largely prioritize on the basis of perceived fit with our core principles, perceived potential impact, and other relevant factors. For example, Evidence Action has expertise in school-based delivery via our Deworm the World and iron and folic acid supplementation programs. As such, if a sourced intervention is delivered via schools, we may be more likely to prioritize it given the overlap with our existing portfolio.

What does the Accelerator process look like in practice?

The Accelerator’s six stages are ordered to enable us to review a high quantity of interventions while focusing the bulk of our capacity and effort on the most promising ones. At each stage, work becomes progressively more intensive. For instance, Stage 1 is primarily focused on the strength of the evidence base and involves only about one day of research. Comparatively, Stage 3 takes approximately one month and includes exhaustive desk research, meetings with subject matter experts, and the development of a detailed cost-effectiveness model. This staged structure maximizes efficiency by ensuring interventions that are not among the most promising are allotted less time and bandwidth.

We also seek insight from other Evidence Action teams to help us spot issues that may result in the discontinuation of research on an intervention as early as possible. This allows us to have a stronger understanding of potential programs earlier than we might otherwise have obtained from desk research alone. For example, our program team might share prior to Stage 4 scoping activities that an intervention is notably a low priority for a particular government. As a result, we may consider different geographies or pause additional research and shift our focus to more promising opportunities.

What are the criteria that the Accelerator uses to guide decision-making on interventions?

At the end of each stage, interventions must pass a consensus decision amongst the Accelerator and relevant program teams on advancement to the next stage. We make this decision based on criteria developed to determine whether a program can be feasibly implemented by Evidence Action (e.g., the government is bought into the program and there are policies in place that would support implementation) and whether it should be implemented by Evidence Action (e.g., we are confident in the program’s potential for impact, it is the best use of our resources, Evidence Action is well positioned to implement this program, etc.).

During early research, the Accelerator focuses most heavily on three primary criteria: strength of the evidence base, cost-effectiveness, and scale of impact. These criteria help us identify interventions that align well with our mission. They’re also key in determining whether an intervention would be a good use of scarce resources, and therefore whether we ought to develop a program to deliver the intervention.

We are also primed to recognize when Evidence Action is not the best organization to deliver a particular high-impact intervention so the limited funding available can be directed to those who can make the greatest use of those funds.

Though we continue to assess interventions on all criteria at every stage, as we progress, the research emphasis shifts to our secondary and tertiary criteria, which broadly cover feasibility and Evidence Action fit. These criteria help us to decide whether it is plausible to deliver an intervention in a given environment based on the resources needed, our organizational competencies, and contextual factors such as the crowdedness of the actor landscape. We are also primed to recognize when Evidence Action is not the best organization to deliver a particular high-impact intervention so the limited funding available can be directed to those who can make the greatest use of those funds.

Our criteria are not stagnant, as we iterate and update them to reflect lessons from prior work. Such iteration led to the addition of criteria concerning organizational alignment. After reflecting on the value of being able to leverage our existing government relationships and our organizational experience with a school-based delivery model during the development of our now-running iron and folic acid supplementation program, we established a working definition for this new criteria and formally integrated it into our framework. Through this cycle of self-reflection, we increase our confidence in our criteria to discern the most cost-effective, high-impact opportunities.

How does the Accelerator develop an intervention into an at-scale program?

In the beginning stages of the Accelerator process, our research is focused primarily on the evidence supporting the intervention itself (e.g., HIV/Syphilis dual tests), rather than the program as a whole (e.g., technical support to deliver and administer dual tests). Though we may consider decision-relevant programmatic factors at an early stage, such as the anticipated complexity of program delivery, the actual program design process begins only after we know that an intervention meets our thresholds for evidence, cost-effectiveness, and scale.

Stage 3 is when we begin to answer the questions of where and how to implement the intervention. By the end of this stage, we will have completed our desk-based due diligence and have an initial sense of program activities for at-scale implementation. However, just because an intervention looks like a good, cost-effective idea on paper, doesn’t mean it’s viable in the real world.

We then conduct in-country visits to scope the feasibility of our program design: is the government bought in? Is it deemed acceptable to the community? What are the expected challenges to implementation and do we think we can mitigate them? Who are the other actors in the space and how should we collaborate? These are some of the key questions we must answer to put Evidence into Action.

Lastly – for interventions that have made it this far – we design and implement field activities to test and refine our program design to a point where we’re comfortable launching at scale. This may take the form of a pilot, or it may be as simple as a small, targeted survey. Once we are confident in our program design, and provided that the refined program continues to meet our criteria, we look towards scaling.

What does it mean if an intervention does not advance to the next stage?

We are commonly asked how many interventions actually pass through the entire six-stage process. Because Evidence Action rigorously investigates so many opportunities and seeks to scale only those programs that are the best use of resources, the answer is very few. In fact, roughly half of the interventions we research in each stage of the framework do not continue on to the next stage. However, an intervention failing to make it through our process does not mean that we deem it ineffective, nor that we necessarily think it is not beneficial.

When an intervention does not meet our criteria or we feel that there are more promising interventions that would be a better use of our bandwidth, we deprioritize it. Given the extremely low probability of making it through the entire framework, most interventions will be deprioritized at some point.

Evidence aside, not every intervention is a good fit for our organizational competencies. For example, bed nets, which have been shown to decrease child mortality by up to 17%, are a tool used to reduce cases of mosquito-borne illnesses and are considered to be highly cost effective. However, given the expertise of other organizations in this intervention, we feel that our resources and competencies could be better applied elsewhere.

Do we reconsider interventions that have previously been deprioritized?

Yes. Sometimes interventions do not meet our criteria at the time of initial analysis, but subsequent new evidence or information may emerge that changes our assessment. Before we move on to other workstreams, we attempt to identify these triggers for revisiting so we can remain up to date with decision-relevant information. For example, we previously examined calcium supplementation for pregnant women. Although we believe it may be an effective tool to reduce adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes, it didn’t meet our criteria due to its expected high costs as well as uncertainty around adherence and the implications for the magnitude of effect. Before deprioritizing this intervention, we determined that triggers to revisit this intervention would include new evidence indicating that low-dose calcium can be similarly effective or evidence on other factors that might address our prior knowledge gaps.

Accelerating the greatest potential for impact

Overall, making the best use of scarce resources is no easy feat. As our CEO, Kanika Bahl, explained to Vox, we are looking for “the unicorns of international development.” We believe that the Accelerator offers a strategic and efficient process for accomplishing exactly that.

Through this unique framework, we’ve optimized and started to scale solutions that could benefit millions of people, including syphilis screening and treatment for pregnant women and in-line chlorination treatment for safe water.

If you are interested in learning more, read about our Accelerator or see GiveWell’s rationale behind its support for the 2022 Accelerator renewal grant.

Topics

Focus Area(s)

- Child and Adolescent Health

- Clean Water

- Maternal and Newborn Health

- Neglected Tropical Diseases

- Nutrition

- Women and Girls